Kenneth Goldsmith: the New York Trilogy

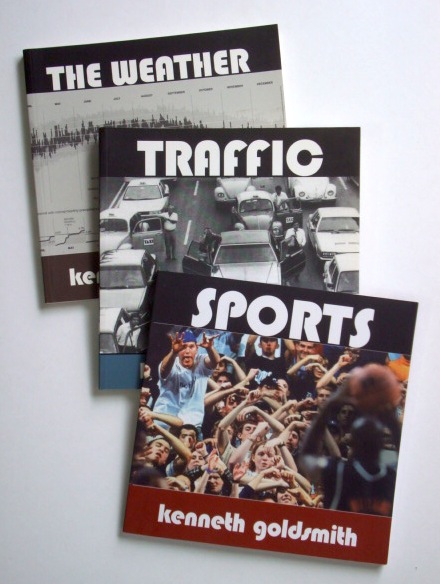

Kenneth Goldsmith’s “conceptual writing” has been the subject of some debate in recent years, much of it fuelled by Goldsmith’s provocative and quotable quotes. In interviews and theoretical essays, Goldsmith refers to his writing as “boring”, “unreadable”, “uncreative”, and even describes himself as “the most boring writer that has ever lived” (from Goldsmith’s Conceptual Writing Journal. See also the extensive bibliography on his EPC site). While such quotes make “controversial” copy for literary journals and fodder for online debates, it seems that much of the critical material on his writing is actually framed by Goldsmith’s own terms. He has shaped the discussion of his own work so that it focuses almost exclusively on the creative processes he uses and his theories about them. To emphasize this focus on the process rather than the end product, Goldsmith stated recently: “You really don’t need to read my books to get the idea of what they’re like; you just need to know the general concept.” (Conceptual Writing Journal) Given that the author died some time late last century, why are we still intent on granting authority to his (sic) ghostly voice? In the following reading of Goldsmith’s recently completed Trilogy – comprising the books Weather (2005), Traffic (2007) and Sports (2008) – I want to put aside Goldsmith’s framing of his work as merely conceptual processes and instead attempt to read the unreadable.

The process common to all three books of the Trilogy is transcription: transferring oral language into written language. In Weather, Goldsmith transcribes a year’s worth of daily weather reports from a radio station; in Traffic, he transcribes a twenty-four hour period of traffic reports at ten minute intervals; and in Sports, he transcribes an entire Yankees-Red Sox baseball commentary. This kind of appropriation and reframing has many precedents in twentieth century creative (or uncreative, if you will) practice, and Goldsmith himself has pointed out many of these — Dada, Conceptual Art, Fluxus, Pop Art, Language Poetry — in fact, Goldsmith’s remarkable Ubuweb can be seen as an ongoing charting of this territory. While the idea of creativity as simply recontextualizing something already out there in the world seems hardly revolutionary in the visual art world, for some reason poetry, at least in its popular understanding, seems inextricably linked to individual expression. Poetry has remained, for some at least, the last bastion of the personal, the private, the intimate and the profound. If we were to adopt this definition of poetry as profound and personal, Goldsmith’s transcriptions of public voices communicating everyday information would seem boring and trivial. But are Goldsmith’s books any more mundane than, say, Richard Prince’s Cowboy series, comprising photographs of cowboys appropriated from various Marlboro advertisements? Are these books unreadable? Perhaps not for a generation growing up in a culture that is comfortable with “uncreative” musical forms such as mashups, regurgitating past design and fashion styles in various manifestations of retro, and the staged intimacy of MySpace and Big Brother.

Although Goldsmith has referred to this trio of books as his “American Trilogy”, the subject matter is actually more specific than that. Despite the implication of conceptual writing’s universality, these works are the product of a particular American city, New York (although many New Yorkers seem to believe that New York is America). The “New York” Trilogy is also more fitting given the specificity of the material Goldsmith appropriates – New York City weather reports (Weather), New York City traffic reports (Traffic) and the commentary from a New York Yankees baseball game (Sports). On this note, earlier Goldsmith books might also be seen in a New York context. In Soliloquy (2001), for example, he transcribed every word he spoke for a week, and given he lives in Manhattan, New York references abound. In Day (2003), he transcribed every word of the New York Times. Rather than read Goldsmith’s New York Trilogy as simply the end product of conceptual processes, it is also productive to read the Trilogy as the documentation of the specific rhythms and voices of twenty-first century New York.

via: http://djhuppatz.blogspot.com.br/2008/08/kenneth-goldsmith-new-york-trilogy.html